Transcript

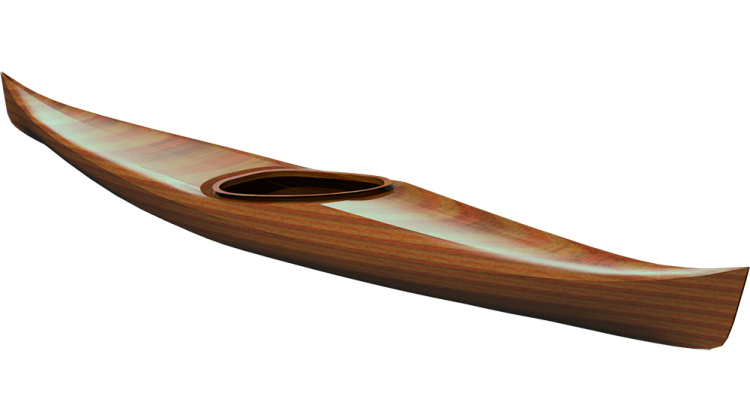

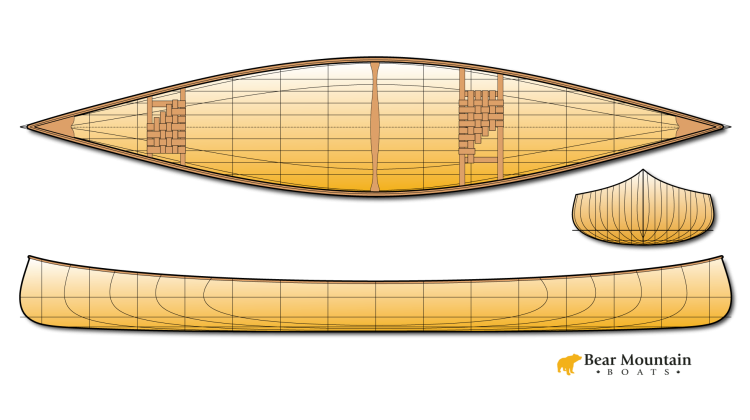

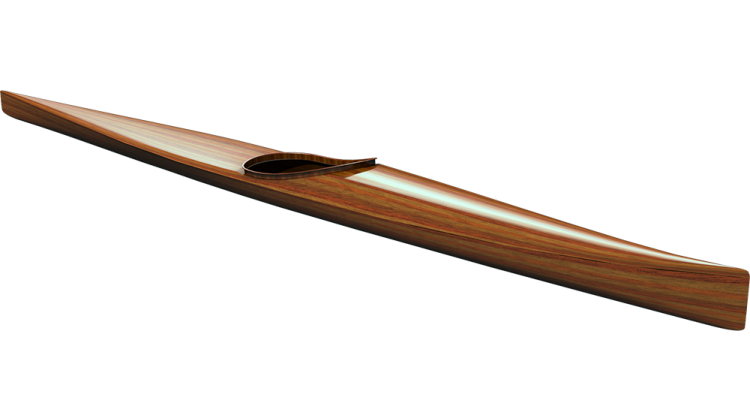

Hi I'm Nick Schade at Guillemot Kayaks, welcome episode number 17 of my series on making the strip built Petrel Play kayak.

In the previous episode I installed the outer stems and di the final fiberglassing. In this episode I'll glass the outside seam, do the final fill coats and then final sanding.

The hatch is flush which makes it hard to lift. A little thumb-dent creates a spot to get a finger under the edge to open the hatch.

I have a small sanding drum I can chuck into my drill. This quickly cuts an indent into the deck along the side of the hatch.

The hatch cover will be secured in place with a couple straps of webbing. The webbing is attached to the deck with stainless steel bolts inserted through holes in the deck. I don't want bare wood exposed to any water that may seep into these bolt holes.

Whenever I penetrate the wood strips I want to seal the exposed grain. With a drill hole, the best way to do this is to drill the hole oversize, fill it with epoxy and then drill the desired hole size through the epoxy plug.

This way the grain of the wood is completely sealed and if someone tries to overtighten the bolts, there is a sleeve of solid epoxy to prevent compression of the wood.

The freshly severed end grain wants to absorb the epoxy. I promote this by heating the epoxy with a heat gun. This lowers the viscosity of the epoxy which allows bubbles to pop and assures the epoxy can soak in as much as it needs to.

I have not yet reinforced the exterior seam where the deck meets the hull. In an effort to keep epoxy drips to a minimum I like to mask off above and below the seam.

By folding in the bottom edge of the masking tape and sticking it to itself, I create a drip edge that forces any drips to fall to the floor before they run down the side of the kayak.

Masking the top is less important, but I find clean up easier it the epoxy layer has a straight edge. I run two strips of tape, one for the fiberglass layer, the next for the fill coat.

In the interest of protecting exposed wood as much as possible, I put a patch of glass into the countersink around the grab loop hole.

I'm reinforcing the outside seam with bias cut strips of the same fiberglass used to cover the deck and hull. To help hold it in place, I pre-wet the surface. I can then stick the strips of cloth to the sides without stretching or distorting them.

After the cloth is wet out, I squeegee off the excess epoxy into a grunge cup.

When the epoxy has set up for a few hours I trim off the excess glass by lightly scoring it inside of the tape with sharp utility knife. Peeling off the green tape pulls the trimmed glass of with it.

I can then apply a fill coat over the seam between the strips of blue tape.

A heat gun pops any bubbles for a clearer finish.

After I think the epoxy has set up enough, I peel off the masking tape.

I was wrong. I didn't wait long enough.

These big ugly drips are annoying, but using a rigid sanding block, or in this case a Shinto Rasp, they aren't that hard to eliminate.

If I were to use a soft block or a power sander with fine grit, I would likely sand through the glass surrounding the drips before knocking them down flat to the surface. An aggressive cutting tool like the rasp just cuts off the high spots, leaving the surrounding surface untouched.

The drips are still annoying, but with the right tool, they don't last long.

The top edge of the seam didn't have the drips, but a quick hit with the rasp smooths the transition.

Now I go over the whole boat with 60 grit on the random orbital sander. I'm using a fairly stiff pad to attack high spots first.

Just like my earlier sanding of the wood, I employ a back-and-forth, followed by up-and-down pattern. The stiff pad does not really conform to the surface, so this pattern assures everywhere on the curved deck gets sanded.

Again, the goal with this sanding session is to knock down high spots. These may include, drips and sags, as well as feathering in edges of added layers of glass. I am planning on another fill coat, so at this stage I interested in starting to level the surface. I want to avoid sanding so deeply that I actually cut into base layer of fiberglass.

After hitting the whole deck with the power sander, I go over it again with a hand sanding block. The goal now is to just de-gloss the remaining epoxy in preparation for another fill coat, so I use a softer pad that conforms to the surface.

Comprehensive sanding includes working on the detail bits such as around the cockpit. I'm still using coarse 60 grit sandpaper.

With the deck complete I flip over to the hull and return to the random orbital sander.

You may have noticed that I never touched the sharp edges with the power sander. I want the feature lines on the deck, at the sheer and at the chine to stay relatively sharp. The power sander would eat right into these, so I come back when I'm all done and take the gloss off by hand sanding.

I also work into the recesses of the deck fittings.

I have found that its not unusual to have tiny pin holes in the epoxy. Surface tension can make it very hard to fill these. What has worked for me is squeegeeing on a thin fill coat, pressing the epoxy into the surface.

While I didn't really thicken this epoxy I did add a small spoon full of colloidal silica to the mix. This doesn't effect the clarity, but adjusts the surface tension enough to keep the resin flat over pin holes.

This thin coat is really just to fill any pin holes. I spread it over the surface, working it into any problems areas and then remove the excess into a grunge cup.

The rest of the deck gets this same treatment, spreading epoxy over the whole surface, being careful not to fill in the deck recesses with drips of resin.

After squeegeeing off the excess, I blast the surface with a little heat to pop any remaining bubbles.

When this layer has tacked up a bit, I want to add a bit thicker fill coat to bury any remaining irregularities.

While thicker than the squeegee coat I just did, I don't need the heavy brushed on fill of earlier coats. I roll on resin to distribute a uniform film, the wet surface is lightly tipped-off with a dry brush to pop most of the bubbles and then flamed with a torch to level and flatten the surface.

Details such as the area around the cockpit are brushed in by hand, being very careful not to leave pools or puddles that will sag or run, making for more sanding work later.

The next day I did the same two-stage fill coat to the hull, first the squeegeed skim coat, followed by a thicker rolled coat.

The quality of your final finish is a function of prep work. Varnish will not fill or smooth a rough surface. A gloss finish highlight any small waves, irregularities or unfair surface with bumps and curves in reflections.

I start the finish sanding with a long board. This somewhat flexible, long sanding block evens out the surface by abrading away the slightly higher spots while bridging over the slightly slower spots until level, fair surface is achieved.

The goal of the long board or fairing sander is to keep sanding away the scratched high spots until they are the same height as the shiny low spots. If you have done a good job of keeping everything fair up to this point, it should take long until you have a uniformly scratched surface with no shiny spots remaining.

Due to the large surface area of the long board, I do need to push a bit to keep it cutting. I strapped the kayak down to the horses to keep it from wandering.

When the hull is done, I flip over the boat and do the same thing to the deck.

The fairing sander is held flat on the boat. I move it forward and back parallel to the strips. Holding it skewed at a bit of an angle helps fair the surface lengthwise as well as across the boat.

Again, I leave the feature line unsanded, working above it and below it in separate operations, never dragging the sander across the sharp line.

With the fairing operation complete I switch back to the random orbital sander.

Going with slightly finer 80 grit sandpaper now, but I'm still using a relatively stiff pad to more aggressively cut down high spots.

Once again, I'm going with my standard, back-and-forth followed by up-and-down sanding pattern to consistently work the whole surface.

I'm still not touching the chine with the power sander.

Flip and continue on the deck.

In spots where the sander does not lay flat on the surface I speed up how fast I move the tool around or throttle down the tool speed to avoid burning through the surface.

The goal now is to eliminate any shiny spots, but without sanding into the fabric. Feathering in the edges of overlapped layers of cloth is OK, but if you are hitting the glass in the middle of a flat surface you may need another fill coat.

When I have completed sanding the whole boat, I add a soft contour adapter pad and switch to finer 120 grit sandpaper.

And sand the whole boat, deck and hull.

Since the surface is now level, the goal of sanding is to eliminate the scratches from the previous courser grit. This goes much more quickly.

After a full pass with the random orbital, I switch to hand sanding with 120 grit to reduce swirl marks. I can now also hit the feature lines, sheer and chine, just sanding enough to remove the gloss.

From there I start working on the detail areas around the cockpit.

I find a soft foam pad works very well for reaching under the coaming and working around the recess.

Cleaning off the sanding dust frequently keeps the paper cutting efficiently and reduces the amount that gets spread around the shop.

I made some sanding tool to help get the hard to reach areas of the coaming.

Upon completion of the 120 grit sanding there is nothing left to do but continue on with 220 grit on a soft pad.

This will be the final sanding prior to varnishing. At this point there should be no shiny spots or dimples left anywhere on the boat. The goal is to eliminate scratches from the coarser paper and creating a silky smooth surface.

Like all the sanding previously, I'm sticking to my systematic left-right, up-down pattern to assure everywhere gets worked evenly.

Even though I'm only sanding out scratches, it still takes some time to be sure the whole surface is in good shape.

The last bit of sanding I do is going of the whole surface with a hand block and 220 grit to reduce sanding swirl. I also hit those detail parts that the power sander won't touch.

Final cleanup starts with a thorough vacuuming to remove as much dust as possible.

The cups of these recessed fittings are a bit tricky. A snippet of sandpaper on the end of a stick does OK at reaching in.

Epoxy is an excellent base for varnish, but through all this work it may have accumulated some contaminants. I first wipe the whole boat down with denatured alcohol. This should clean off any epoxy related residue.

I follow the alcohol with a mineral spirits wipe down. Mineral spirits are compatible with the varnish and should clean off any oily residue which might interfere with the varnish curing.

And that will be left for the next episode where I'll apply several coats of varnish, with some more sanding in between.

If you are enjoying this series and would like to see more like it, please hit like, subscribe and share this video with your friends.

Once again, thanks for watching and happy paddling.