This videos details the process of building a Solo microBootlegger kayak, emphasizing the balance between aesthetics and practicality throughout the construction.

- Initial Challenges: The author, Nick Schade, discusses the difficulties of starting and maintaining momentum on projects, particularly when faced with interruptions.

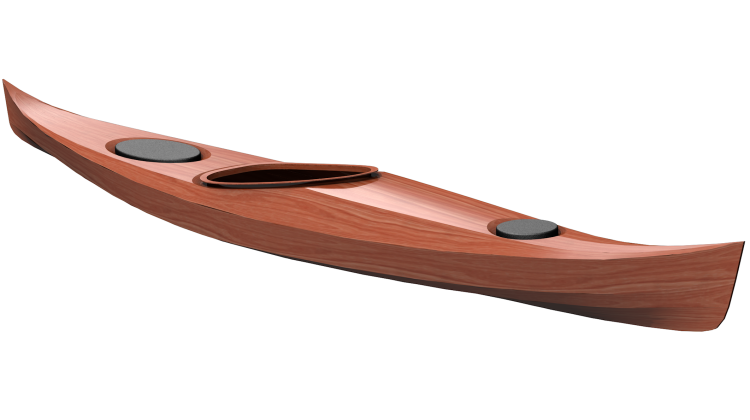

- Kayak Design: The Solo microBootlegger is a 14-foot recreational kayak designed for comfort and stability, commissioned by a client to honor their deceased father.

- Construction Techniques: The kayak is built using a strip-building method with western red cedar, chosen for its beauty and lightweight properties. Nick opts not to book match the strips to save time.

- Balancing Perfection and Functionality: Nick emphasizes the importance of practicality in building a kayak that can be used without fear of damage, arguing that a perfect-looking kayak may become unusable.

- Skill Development: The video highlights the learning process involved in boat building, suggesting that beginners should set realistic expectations and focus on mastering basic skills before tackling advanced techniques.

- Artistic Elements: After constructing the basic kayak, the author incorporates artistic elements, including a marquetry bald eagle head, which requires careful planning and execution.

- Dealing with Mistakes: Nick recounts a setback with the inlay that required a fresh start, illustrating the importance of learning from mistakes and adapting solutions.

- Final Touches: The video concludes with the completion of the kayak, including protective coatings and aesthetic details, underscoring the satisfaction of creating a functional and beautiful boat.

Chapters

- 0:00 - Personal Project Introduction

- 0:52 - Kayak Project Overview

- 1:54 - Boat Building Process Details

- 12:18 - Artistic Detail and Problem Solving

- 17:49 - Project Completion Philosophy

- 20:35 - Final Reflections

One of the hardest parts of any project is getting started. It doesn’t matter if it’s building a boat or editing a video, there is always a bit of inertia that must be overcome before I get myself motivated to start. But even worse, can be restarting.

Hitting a glitch in the middle of a project that causes you to step back and take a break can result in a big delay or even a situation where you never get back to it. I find I work best when I concentrate on one project and keep at it until done. I’m not good at multitasking, I like to focus and maintain momentum. Narrating the voice over for a build I did a couple years ago while trying to build a couple other boats throws me off, but I’m doing my best to keep it together.

Hi, I’m Nick Schade, welcome back to the Guillemot Kayaks Workshop. In this episode I’m building my Solo microBootlegger design. This is a commission I received from a client out on the west coast. Their dad had recently passed away, leaving them with a bit of money they decided to use to create something to remember him by.

The Solo microBootlegger is a stable 14’ long recreational kayak that is comfortable and relaxing to paddle. It is stable, has a nice roomy cockpit, and moves along easily at a moderate pace. It’s good for anyone looking to go out in a harbor, bay or lake.

In choosing to have me build this kayak, the client had to make some choices about how high a level of finish they wanted for their kayak. They wanted a kayak they could paddle, their budget was limited but large enough they could afford a custom-made kayak. They wanted a beautiful reminder of their Dad, but not something to just hang on the wall. In other words, they wanted an artistic kayak, not kayak-shaped art.

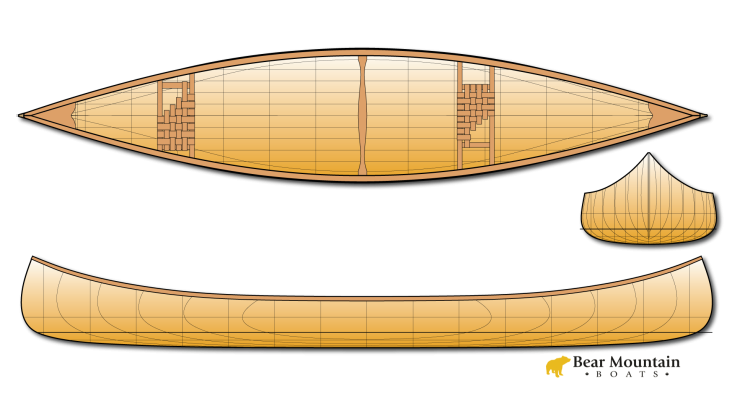

The Solo microBootlegger is a strip-built design. Strip-building creates a beautiful boat from thin pieces of solid wood bent around forms. I chose to use western red cedar due to its gorgeous color, good strength and lightweight properties. It also reflects some of the natural environment where the client will use the kayak.

If you’ve watched some of my previous builds, you may have seen me “book match” the strips. Book matching involves keeping the strips in the order they came off the original board and putting consecutive strips on either side of the boat to create a repeating, mirrored pattern.

I’m not doing that.

Bookmatching requires careful work and, as such, adds quite a bit of time to the construction. While book matching looks nice, the western red cedar is beautiful even without that added effort.

Speaking of balancing aesthetics with practicality, you'll notice I'm using staples to temporarily hold the strips to the forms while the glue dries.

Again, you may have seen me build boats where I didn’t use staples because I didn’t want the little stable holes, but this boat is going to be used. It will get scratched up over time.

The goal is to make a beautiful boat, not an object so precious that it can’t be used. By using staples, I save some time making the kayak, save the client some money, and make it easier to feel comfortable subjecting it to a rocky beach landing.

I’ll do a bit to take the beauty to the next level later, but for the basic construction, I’m keeping it simple, affordable, but hopefully elegant.

I’ve said before, the amount of time you put into a project like this can be nearly infinite. Every step of the way, there are things I could do to make it more “perfect”. There is always something that can be upgraded. Everyone endeavoring to make something must decide where the need to be better meets the point of good enough. After a point, the incremental cost of making it better does not justify the slight improvement.

The key is in how you define perfection. There is the platonic ideal of flawlessness where every joint has no gaps, the wood grain is the paragon of matching, the hull is faired to mathematical precision, etc.

But we are creating a kayak that will be used. To the extent the preciousness of the finished product inhibits your willingness to allow it to be scratched, that “perfect” boat may become perfectly unusable and thus, not even a good boat, let alone “perfect”.

What constitutes perfection in this kayak is: when my client is out on the water, they forget about the boat, but being out there reminds them of their father. I don’t want worries about scratching the kayak to detract from the pleasure of being there, I want the kayak to enhance the experience.

I’m looking to balance beauty with practicality.

For instance, I’m using square-edged strips instead of cove and bead. I feel I can get tighter, better-looking fits by carefully beveling each strip to fit the next one.

I’m using my RoboBevel tool to make this tight fit. It’s taking me about 20 minutes to install one strip here.

I could have saved 5 to 10 minutes if I’d used cove and bead strips for “pretty-good” seams between strips, or I could spend another 20 minutes to make that fit even better. I decided that doubling the time once was adequate to be good enough, and that doubling the time again would not have resulted in a sufficiently better appearance to justify the time. I could do better, but not enough better to be worth it.

My priority is to make sure the kayak meets all the physical requirements of being a safe and reliable kayak that will perform well on the water. I want to do that in a way that looks great, but once I have achieved the necessary strength and performance, making it look slightly better starts to become less urgent.

These kinds of decisions are part of any project. While it may not be specifically whether to use staples or not, there are always choices between doing it the absolutely best way possible vs getting the project done on time and within budget.

I’m building this kayak for a client, so if I want to get paid, I’m going to get it done regardless, but working on your own projects at home, one of the biggest risks is, you run into some hitch and the project stalls out.

What exactly the problem is can vary, sometimes it’s something broke, or maybe something didn’t fit right, or it just doesn’t look good. If the project you’re trying to do is new to you, or has you outside your comfort zone to begin with, figuring out a solution or a path forward can be overwhelming. You may put the project aside until you come up with a plan, and then the whole thing drifts off the bottom of your project list and 10 years later you toss the project in the chipper.

One of your tasks when you’re deciding on a project is setting yourself up for success. And that can mean setting reasonable expectations for your project. If you have never built a boat before and you’re impressed by what that guy on YouTube made look really easy, it’s worth noting that a task that is easy for someone with experience may not be as easy for a first-time builder. Setting yourself up for success can mean matching your expectations to your experience level.

While staple-free construction and that book-matching thing may be exactly the look you want to achieve on your first build, each one requires a set of skills that you will need to learn while building. You will already be learning a bunch of basic skills that have a more immediate impact on the look of your finished boat.

Getting the strips fitted together without major gaps is an achievement, but the most impact you will have on the finished look will be after all the wood is in place and you start fairing and sanding.

The book matching I’m doing here on the back deck, installed without staples won’t look great if I don’t follow through.

I still need to get a clean and smooth layer of fiberglass and epoxy on that wood, fill the weave with a bit more epoxy, and sand and fair that surface and apply varnish. Each of which takes practice to do well.

A good finish will make the wood look spectacular even if your woodworking skills need work. But regardless of how good a job you do with the finish work, chances are excellent that the boat will float even if you didn’t match your expectations during the build.

If you allow yourself to become discouraged with your results as you work on the project, you run the risk of not finishing it. Remember, nobody ever learned anything by doing it right the first time. Making mistakes is expected; learning from them and improving as you go is integral to the project. The struggles you have during the project are what make the project worth doing. If it were easy, everyone would be doing it, and success wouldn’t be much of an accomplishment.

I’ll tell you right now, your standards are high and you aren’t going to be completely satisfied. I’ve been building kayaks for about 40 years now. I’ve made hundreds of boats. While I have been very happy with a lot of these boats, not one of them has completely fulfilled everything that I wanted to accomplish with the build. I’m always left thinking about how I can do it better next time.

For those of you watching who are not familiar with the boat building process, I suppose I owe you some sort of explanation. As I mentioned before. I am making a strip-built kayak. What you have watched me do so far is taking a bunch of thin, narrow strips of western red cedar and assemble them around a form.

The strips are 3/16” thick (about 5 mm for those who understand sensible units) and ¾” wide (19mm). I have used standard woodworking glue to hold them together. They were temporarily held to the forms with some staples, after pulling the staples there is nothing else attaching them to the forms.

While the wood is still on the forms, I plane and sand the surface smooth and fair. Wetting down the surface helps raise the grain before the final sanding.

The wood by itself is not particularly strong. While its not weak, it is less than ¼” thick and as such won’t stand up well to the aforementioned landing on rocking beaches.

This method of boatbuilding gets much of its strength from fiberglass. Fiberglass is exactly what the word says, fibers of glass.

I didn’t glue the deck and hull together. This allows me to remove the deck and place the hull and deck each on separate strong backs. I did struggle a bit to get the deck out this time.

The longest part of the fiberglassing process is the time it takes the epoxy to cure. Epoxy bonds the glass fibers to the wood. By, placing the two parts on their own form I am able to wet out the fiberglass on both pieces on the same day. This saves several days in the building process.

The white fabric is 4-ounce fiberglass. In this form fiberglass is light and smooth with silk-like texture. Unlike some fiberglass materials, it does not cause itching when you handle it. It is very flexible and easily conforms to the shape of the kayak.

YouTube is full of folks making stuff with epoxy. If you didn’t know better you might think epoxy was invented to make river tables. But, in reality it is a kind of glue. It was originally intended to bond things together.

In this application, epoxy bonds the fiberglass to the wood. Epoxy by itself is not very strong. Raw fiberglass is flexible and without structure. While wood is pretty strong it really doesn’t like water. Combining them all together, epoxy bonds the fiberglass to the structure of the wood, the fiberglass binds the wood together and the layer of fiberglass plus epoxy protects the wood from water. The resulting composite material is lightweight, and rugged and because the glass is actually clear like a window, the epoxy makes the glass disappear so all you see is the wood.

After wetting out the fiberglass with a coat of epoxy, the surface of the boat still shows the texture of the fiberglass fabric. After curing for a couple hours another coat of epoxy starts to fill that weave texture so the natural beauty of the wood shows through.

With the epoxy cured on the outside, the deck and hull are now strong enough to remove from the forms. I make another set of cradle forms to hold the pieces while I scrape, sand and fair the interior.

Just like the outside, the inside gets a layer of fabric reinforcement. I include a bit of carbon fiber in the cockpit seating area to add some stiffness and strength. I also just think it looks cool. While the white fiberglass disappears, the carbon fiber starts black and becomes blacker.

Once again the fabric is saturated with river table juice to bond it all together.

The excess cloth sticking up along the edges is easy to trim off with a sharp utility knife.

The cockpit area needs a coaming rim to add strength and to create a perimeter where a spray skirt may be attached. This rim is made of the same western red cedar strips and reinforced with fiberglass.

Again, overall for this build I kept the stripping pretty simple, but I did want to do something that stepped it up a bit. I opted to book match the back deck and installed it without staples. This is a pretty easy area to strip and as a visible part of the kayak it makes a nice impact on the overall look.

Beyond that, the client wanted a bit of artwork. Having established the basic structure with an eye toward efficiency, we could now focus on the artistic elements that would make this kayak truly special. After discussing several ideas, we settled on a marquetry bald eagle head.

The eagle head image is based off a photo I found online. I then adapted it to cut from veneers. I have a small collection of 1/16 inch thick veneers I have cut myself over the years. The goal is to match the wood color and grain to match the feathers and beak of the eagle.

I traced the patterns onto each bit of veneer with some carbon paper and taped it in place in the growing assembly.

Tilting the table and stacking adjacent pieces allows for the kerf width of the blade so the pieces are tight together. Scorching the pieces of veneer in hot sand allowed me to create a some shading to add a bit of 3-dimensionality.

With the artwork all cut out and held together with tape, I then traced the piece onto the back deck, centering it in the back hatch area. I scored around the perimeter of the artwork, cutting through the glass into the wood. I then used a router to recess the surface down by the thickness of the veneer.

The strips on the back deck were 3/16 inch thick and the recess for the veneer chewed into a 3rd of that, leaving the back deck 1/8 inch thick in the veneer area and pretty flexible. I thought about several strategies for clamping the inlay in place. What I settled on was vacuum bagging. I didn’t want to distort the deck shape with a clamp and I figured the vacuum would not put any pressure on the shape of the deck.

In my ignorance, I reckoned that standard yellow glue would be easy and dry pretty quickly, so I buttered up the back side, lined up the inlay, installed the bagging film and sucked it down with the pump.

After the glue dried, I removed the bag and started cleaning all the tape off. Well, I was not too happy. As anyone who has worked with water-based glues and thin pieces of wood may know, humidity can cause wood to move.

The inlay was all wrinkled and lifted off in various places. I tried ironing it down. Heat will soften and re-activate PVA glue. While I got some more bits to stick down, it was still pretty awful.

I tried sanding it level to see what it looked like. After burning through in a few spots yet still having uneven areas, I had to decide that it had to come out - a perfect example of knowing when to cut your losses and start fresh.

I came up with several ideas to fix it: cut another piece exactly like the first and try to lay it exactly above the failed inlay, make a slightly larger version, or put some sort of border around it.

I didn’t think I’d have much luck getting a new piece to match exactly. There’d be bits showing around the edges. If I went with a slightly bigger, because of the complex shape, it probably wouldn’t to hide all the old bits.

As you can see, decided to place the inlay within a shield of book-matched mahogany. This shield would hide everything behind it. So, it was back to the jig saw to cut another inlay. I do enjoy the process of cutting out the artwork, but it is frustrating to do the same thing twice.

I got the new marquetry cut out along with the surrounding shield. This whole thing then needed to be inset to the 1/16 inch thickness. Most of the first effort was cut away in the process, but the remaining bits would end up completely hidden.

Having learned a few lessons from the first attempt, I cleaned off all the masking tape on the artwork and then did the vacuum bag again. This time using epoxy. I placed some perforated release film over the artwork and a bit of infusion flow media as a bleeder and sucked down the vacuum again.

There were some ridges of epoxy from the wrinkled film, but with a bit of scraping and sanding, the whole thing was flush and smooth.

Because the deck was so thin and since all the sanding had introduced some non-fair areas, I decided to add two layers of glass over the veneer. This would stiffen up the hatch so when I cut it out later, it will better maintain its shape. The thicker glass will also let me do some more aggressive fairing sanding without risking sanding all the way through both layers of glass.

I used heat to lower the resin viscosity and a bubble roller to make sure there was no air trapped between the layers. The result looks good. The mahogany behind the eagles’ head looks good. I even got the centerline to match the centerline of the deck. There are things I would do differently if I were to do it again, but I learned a lot of good lessons.

If this were a casual hobby project, a failure like this after all the effort of stripping up the kayak, glassing the inside and out, and all that time carefully cutting the marquetry, could easily feel devastating. It is important to remember that almost every mistake is recoverable.

The difference between an experienced craftsperson compared to the beginner isn’t that the experienced person doesn’t make mistakes, it’s that they’ve learned how to fix their screwups. Experience provides the ability to focus on the goal and finding a way to get there.

With that crisis averted, I had to get on with the project. I always find this stage of the process where the deck and hull are essentially done tends to drag on. There are a lot of small parts of the process that benefit from access to the interior and exterior at the same time.

The coaming needs completing. The hatch needs to be cut out, the hatch lip installed, edging is put around the hatch, and everything is sealed under glass and epoxy. I strive to have no wood that is not under a layer of fiberglass and epoxy.

When the bits and pieces on the interior are completed, I protect the whole insides with a bunch of coats of varnish. I have been using a water-based varnish for this because it dries quickly while adding good protection.

Finally, the deck and hull can be joined back together on the inside. After adding outer stems and a bit of sanding, the outside seam is covered with a piece of fiberglass across the whole bottom. This adds protection from rocks and stiffens up the hull a bit more.

As is often the case with my videos, my diligence at capturing every step of the process tapers away as I near completing the boat. This is usually due to an impending deadline. Setting up a camera and making sure the audio is being captured slows down the whole project

So, while the finishing process involved several more weeks of detailed work, including sanding the epoxy, applying varnish, sanding varnish, applying more varnish, some more sanding , followed by other setting up and fitting out will move past in a flash of video editing.

My goal of creating a beautiful, yet practical boat for my client was accomplished. I favored efficiency in the construction of the basic shell of the kayak, prioritizing the performance of the boat. This gave me the time to concentrate on aesthetic details where they would have the most impact.

Making mistakes is part of any project truly worth spending time on. If you’re doing a project for your own personal satisfaction, don’t let those mistakes distract you from the final goal. If you are working on a project professionally, mistakes need to be calculated into your expenses and fees. Your client or customer is paying you for your experience, which includes the mistakes you learned from in the past and the cost of you taking on new risks and expanding your skills.

It doesn’t take a failure as drastic as my inlay mistake to derail a project. There are partially finished projects in basements and sheds around the world that stalled out because of some minor hiccup during their making. Set yourself up for success by setting realistic goals, and then when you goof something up, sit in your moaning chair for a spell and get back to it.

I am really pleased with how the kayak came out. While there’s nothing fancy about how the wood is laid out, that isn’t necessary. The wood speaks for itself, it does not need me to do anything to dazzling for it to look beautiful.

The solo microBootlegger has an elegant shape reminiscent of a classic runabout. It doesn’t need ornamentation to look good. Keeping it simple works.

On the day she launched it, my client held a little ceremony to remember her father. With the eagle on the back deck she decided she would keep on paddling until she saw an eagle and saw one within minutes. The only complaint was from her husband who has trouble keeping up. Her Dad would have approved.

Thanks for watching. If you would like to build a small boat yourself, you can find plans for the Solo microBootlegger and other designs at my website Guillemot-kayaks.com. I would like to thank my Patreon supporters for the help making it possible for me to do videos like this.

Until the next time, have fun building.