I consider myself a cautious paddler, yet I have been "boarded" by the Coast Guard 3 times in the past year. "Boarding" is what the Coast Guard calls it when they stop you on the water for a safety check. There are no grappling hooks involved and the number of passengers on my kayak do not change. Instead they just stop you and ask a few questions, trying to ascertain if you are prepared for going out on the water.

In each case it was during the winter, the weather was cold, the water was cold, almost nobody else was on the water, and in one case the water was sufficiently rough that I had to tell the crewman that I could not comply with his requests as it would put me in danger. In other words, it was not unreasonable for the Coast Guard to be concerned about my safety, even if sometimes I know more about what is safe than the crewman.

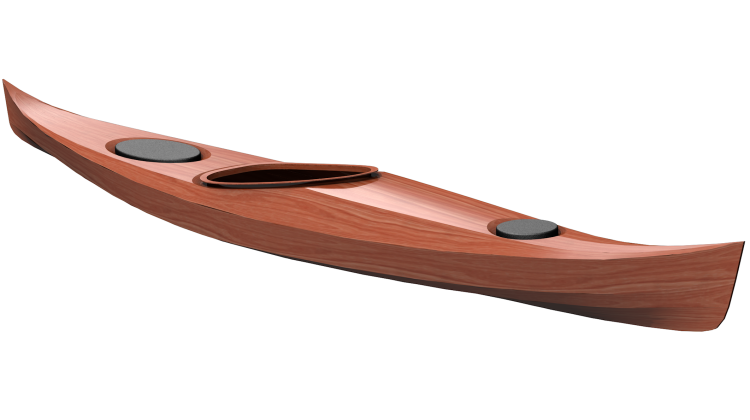

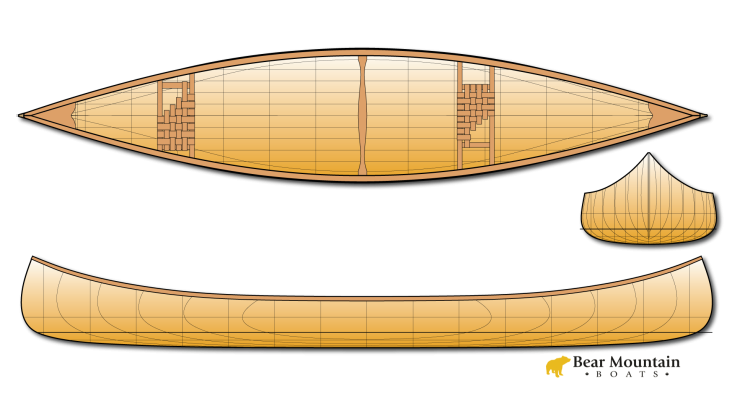

I routinely go kayaking in the winter to play in high winds, strong currents and large waves, i.e. days when most sane people would not consider getting in a kayak. Yet, I still feel I am a cautious paddler. But it is easy to become complacent in my ability to do the things I love to do. Catching a wave and surfing in a tide race is fun, but it is not without risk. Much of the fun is tied tightly to that risk. Causing a narrow boat to ride the energy of rough water is enhanced by the fact that it takes skill and experience to make it happen.

Gaining that skill and experience can only be accomplished by pushing my limits, and finding those limits requires exposing myself to risks. The hope is I can contain the risks in such a way that I stay reasonably safe while still finding and learning new skills. I try to be cautious by keeping in mind the old investing saying: "Past performance is no guarantee of future results." I.e. don't be complacent.

Avalanche School

I recently read an article in the New York Time titled What I Learned in Avalanche School. The author of the article had just gone for training about how to be safe in avalanche country. One quote sticks out:

... by taking an avalanche-safety course, we had statistically increased our chances of being killed in an avalanche.

At first blush this seems counterintuitive: shouldn't safety training make one safer? But, if you think about the risk of death from jumping from a perfectly good airplane, it is clear that most rational people would first take parachute lessons, and your chances of going splat is greatly increased by first learning how to jump.

But it is more insidious than just that. Most of the people caught in avalanches created the avalanche they were caught in. Its not that they were just having fun skiing when a random avalanche dropped in. Instead these people looked at the conditions, evaluated the risk, then choose to push off, and their presence caused the avalanche. With hindsight it is usually clear that the evidence they looked at was sufficient to predict significant avalanche risk, yet they chose to go forward regardless.

Avalanche science seems to be mature enough that with good data and training in interpreting that information, getting a good sense of the risk is a relatively straightforward proposition. While maybe not exactly easy, a skier on the mountain can make reasonably accurate predictions.

What is more complicated is the vagaries humans making decisions. The human factors involved when deciding when to proceed and when to turn back often lead to poor choices.

On the day you want to do something various thoughts go through your mind:

- This is my home venue, it won't let me down

- All my friends drove all day to get here, I can't let them down

- This is what we planned to do, I can't turn back now

- I'm with this expert, if he thinks its safe, it must be safe

- This is my one day that I can do this, its now or never

- We are having so much fun, lets keep going.

These are what have been called "Heuristic Traps". Heuristics are how we process experiences and turn them into knowledge. They become traps when they lead to poor decisions. The avalanche science community has developed the acronym FACETS to help remember them:

-

FAMILIARITY - Parties traveling in familiar terrain made riskier decisions than parties traveling in unfamiliar terrain. This effect was especially pronounced for parties with substantial experience and training.”

-

ACCEPTANCE - Group members want to be accepted by members of their parties. “Accident parties that included females made riskier decisions than parties of all males. The effect was most pronounced in parties with little avalanche training. It is notable that these were precisely the parties in which women were least likely to participate.”

-

CONSISTENCY - Parties that were highly committed to a goal – a summit, ski slope or an objective in deteriorating weather – made riskier decisions than parties just out for a day. This effect was most pronounced in parties of four or more.

-

EXPERT HALO - Accident parties often contained a de facto leader – someone who was more experienced, older, or more skilled. Novices were were more likely to follow the leader into dangerous situations than when novice groups made decisions by consensus.

-

TRACKS/SCARCITY - Parties took more risks when they were racing a closing window of opportunity, such as competing with another group for first tracks.

-

SOCIAL FACILITATION - When skilled parties met other people in the backcountry, they were more likely to take risks than parties that were less skilled. This effect was most pronounced in groups with the highest levels of training.

These are forces weighing on your mind as you attempt to make a good decision. The human mind also has cognitive biases that tend to work against our making analytical decisions. For example, we tend to have more confidence in information that confirms our existing beliefs. This confirmation bias may cause us to have more faith in evidence that says move ahead when we already think moving ahead is the better idea. We will put more effort into finding reasons to do the thing we already want to do than in finding reasons to stop.

There are lots ways the human mind work against our making the best decisions and it can be even harder to make good decisions when tired, hungry, thirsty or under some other form of stress. The best time to make safety decisions is often before you head out on your adventure, when you are strong and thinking straight.

FACETS of Sea Kayaking

I believe the first time I heard about the FACETS acronym was from Jeff Allen when he was here for Autumn Gales this past fall. He was using it in the context of planning a day out on the water. While the risks of sea kayaking are substantially different from skiing the avalanche zone, the heuristic traps one can fall into are the same, and the best way to avoid them is to be aware of your own ability to fall for the traps and avoid becoming complacent.

One difference from avalanche safety is the dangers in sea kayaking are not typically hiding under a layer of soft fluff only to be release by the inadvertent breaking of an almost invisible fault line. The science of what creates risky conditions is more out in the open, available for anyone to see. Tides can be predicted years in advance, the contours of the ocean bottom do not generally change rapidly, and despite our complaints, weather forecasting is amazingly reliable.

If there is going to be rough water created by a tide race, with a little training you can learn to be pretty accurate in predicting when and where it will happen.

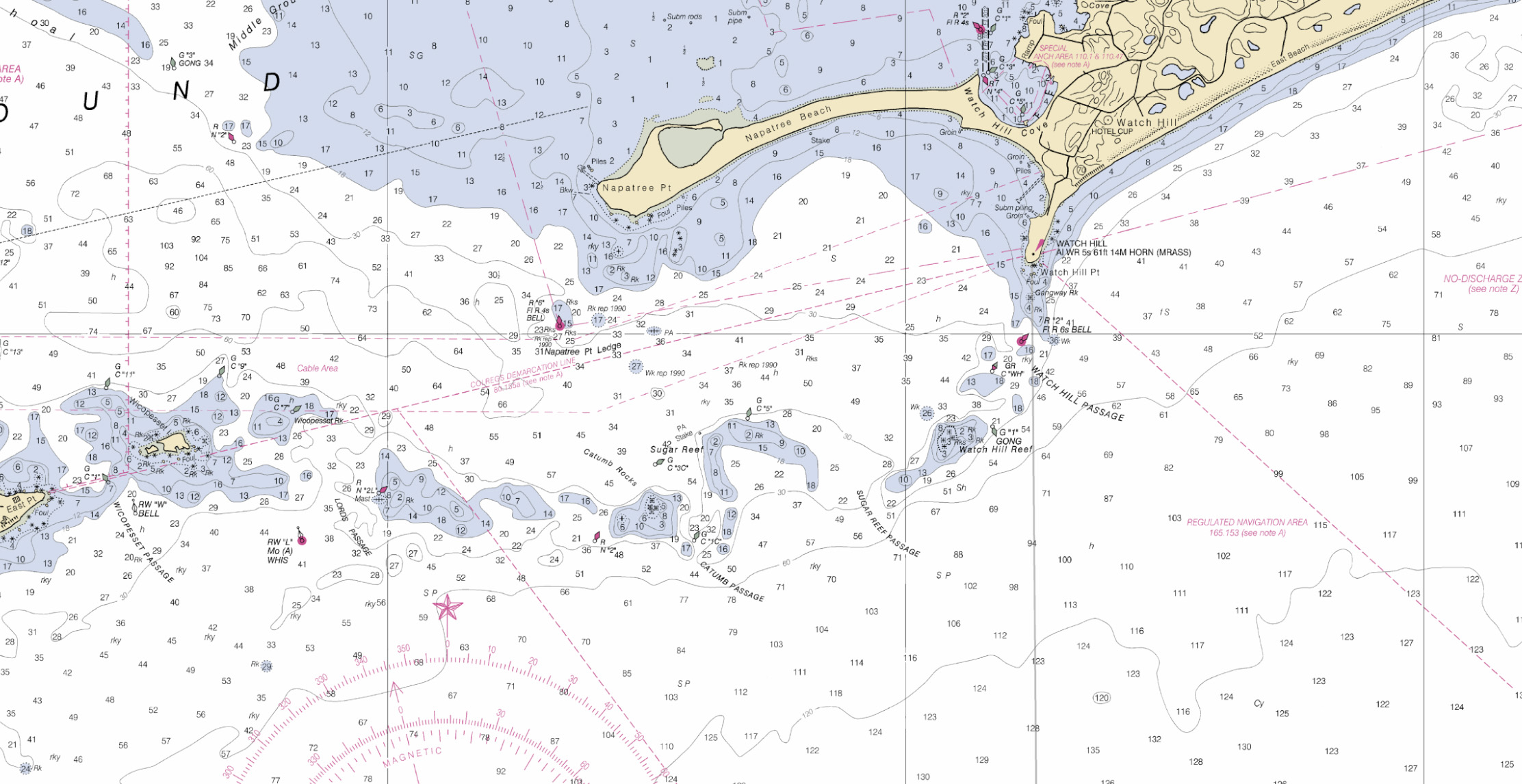

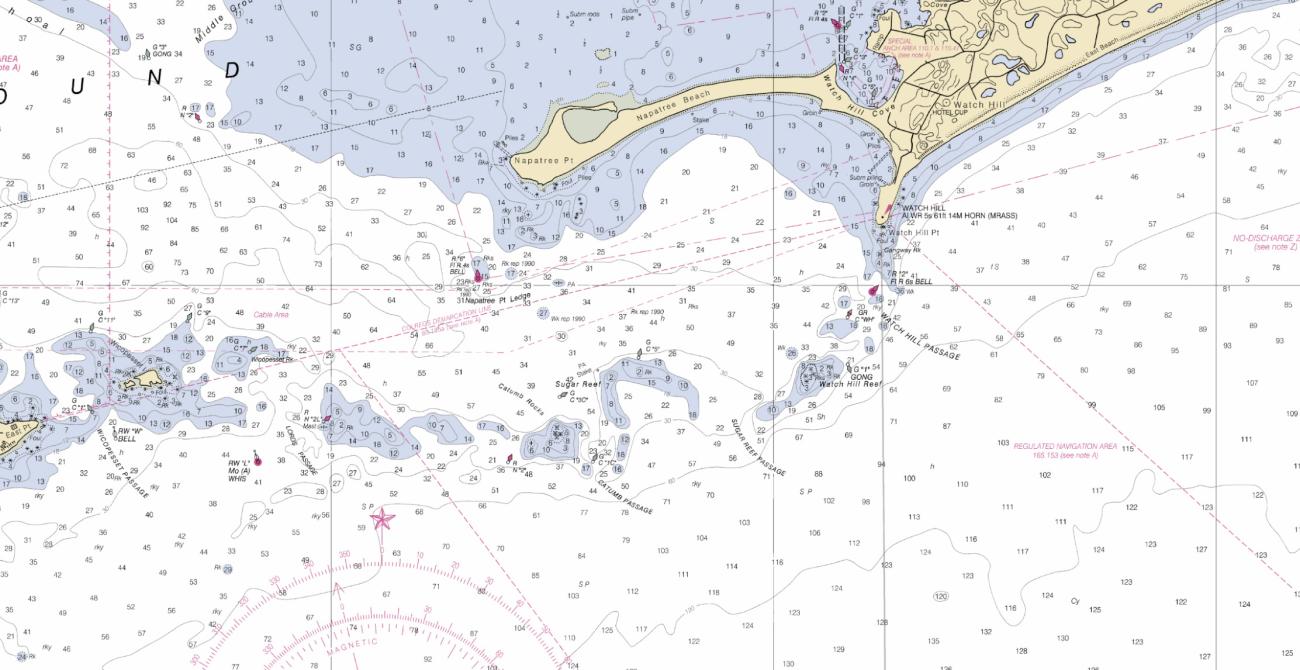

In the afternoon after eating Christmas dinner Gerry Polinsky and I came up with a plan to catch the strong ebb flowing from west to east over Sugar Reef pushing against an easterly wind and see if we could find some nice tide race waves to play in. Feeling a little plump from all the holiday eating we launched from Stonington Point, cut across the rubble at the eastern end of the eastern break water and headed out past the Napatree Ledge bell buoy. The current was already pulling us quickly to the east and the easterly wind was creating some nice chop as we drifted down on stake at the northwest point of Sugar Reef.

On the ebb, the reef creates a fairly distinct headwall of smooth waves followed by a lumpy field of waves extending eastward several hundred yards. This day the wind was blowing 10 to 15 knots, enough to push the ebbing tide into a venue of chest to head-high waves surging and breaking as they progressed east to west towards the front of the field.

This is what we came for. The exercise involved paddling and drifting down into the field then turning back into the current and seeking a line where the waves will surf the kayak forward back up to the front of the field. With a series of quick sprints followed by fast runs and aggressive turning it is possible to move rapidly against the current for an exhilarating run until back to the smooth water upstream of the reef.

While the goal is to make this run with the minimum of effort, there is typically a goodly amount of paddling really hard only to have a wave smack your kayak off course and shoot you off in some undesirable direction following by a lot of hard ruddering and sweep strokes intended to bring yourself back on line and headed towards the steepest waves at the headwall of the field of waves. If all goes well, you may end up with the bow of the kayak buried a foot below the surface with green water all the way up your spray skirt.

I said at the beginning that I feel that I am a cautious paddler. While this may not sound to everyone as the actions of someone being cautious, we regularly come out to Sugar Reef for exactly these conditions, and I have become quite familiar with way the waves work at this location. There are familiar eddies and lines of waves that are consistent in their location and how they progress through the field. These are my home waters and I know what to expect.

The risks are different in the winter. Paddling in rough conditions, capsize is always a possibility. The air and water are cold. Wind chill can disable your hands. A long swim can shut down all your muscles or bring on hypothermia. I have a reliable roll so I feel the chances of a long swim are low, but cold water shock could cause my roll to fail. I wear a drysuit but dressing for a prolonged swim can be too much to wear when you are active.

Paddling with Gerry I know I have someone strong and capable should I need assistance, but in rough conditions, it is easy to lose touch with the group and a kayak or swimmer can be hard to spot from any distance. I carry a whistle and a radio, but with any wind a whistle doesn't have much range. Batteries die and saltwater can short out even waterproof VHF radios. In the winter there are not many other boats on the water so any help from a third party may be a long way off even with a functioning radio.

Kayaking in December involves a higher level of risk exposure than the same location on a warm summer day. But, I have experience with the conditions and feel it is not a great risk. I think I can still be a conservative paddler and go play in tide races in the winter. With a combination of planning, skills and experience, I feel confident that I can manage the risk to the point that it isn't much worse than driving a car to the launch.

A bit further to the east is Watch Hill Reef. It is not much farther away from our launch but we don't typically work our way down to it when we head out for tide race play. I honestly don't remember our reasons for not going to Watch Hill Reef, but we stopped going years ago and have fallen into the habit of going for Sugar Reef or Catumb Rocks when we are seeking fun conditions in this area.

This habit developed before Gerry joined us regularly and we recently did do a quick exploration of the reef on a very calm day. Gerry was interested in seeing what it looked like when there was wind opposing tide situation creating a tide race.

After paddling at Sugar Reef for about 30 minutes, Gerry proposed we head down to Watch Hill Reef to see what was happening.

So, here is the situation: We know the conditions are good today, the wind and tide don't combine like this very often, especially during the winter. Gerry has a long drive from where he lives to Stonington where we launch. He has invested more than I had to get to the put-in. We are both strong paddlers, confident in our ability to handle just about anything the ocean wants to throw at us. The conditions at Sugar Reef were great, they could be better at Watch Hill Reef.

I told Gerry I didn't want to go. I said "We are having fun here, we don't need to push it."

Watch Hill Reef is a bit farther down the tide stream than Sugar. As a consequence the flow can be expected to be a bit faster. The change in depth is greater. At Sugar the rocks are well below the surface, where at Watch Hill they often break the surface. The faster flow with shallower water makes for a larger gradient in the speed of the water in the tide race which means the waves can be bigger and the waters more chaotic. Since the reef is farther down stream it means the paddle back against the tide is longer. Not a whole lot longer, but we are in a human powered craft.

The question becomes, "What are we doing here?" We were at Sugar Reef to play. Going to Watch Hill would be to explore and learn. My feeling was, let's stick with having fun and leave the exploration to less risky day. Gerry accepted with only a little push back.

This day it was fairly easy to avoid some of the heuristic traps. At Sugar we were in very familiar territory, going to Watch Hill was not as familiar. Gerry and I have paddled together long enough we don't have too much to prove to each other, I was not worried about him accepting me. Our goal had originally been Sugar Reef, so Watch Hill would have been a bit of mission creep. We weren't following some acknowledged leader, we paddle together collaborative partners. And being December 26th in New England we weren't seeing anybody else out there having more fun than us so it was easy to stick to a conservative plan.

I don't know if it was the right decision. It would have been good to gain some experience and local knowledge of the area by exploring a bit. Part of the joy and pleasure of being out on the ocean in the winter is the chance to see nature in a way not accessible to most people. Access to that experience requires some risk and the risk serves to heighten the experience. The additional risk of going another mile down stream would have been minimal.

After a couple hours playing in the waves at Sugar Reef, I was pretty exhausted. Gerry related how on one of the rides felt like getting whipped around the corner of a rickety roller coaster with his head getting whiplashed as he was smacked by waves from either side. Gerry tweaked his shoulder a bit on his last ride and I had to fight a bit to get free of the current at the reef at the end. In other words we had a rollicking good time.

The destination of any kayaking trip or wilderness adventure is to get back to the car safely. The goal is to reach this destination as inefficiently and in as exciting a route as possible, while still getting back to the car. We probably could have eked a bit more adventure out of the day, but we had fun and were back to the cars before dark.

Our local group of paddlers have been playing in this area year-around for maybe 20 years. We are well prepared with proper clothing and safety gear. We have multiple communication options, and importantly we have the experience to know what to expect on the water and how to handle it when we get there. Training and practice has prepared us to deal with most mistakes. We have done everything we can to minimize the need for luck, but luck does still play a part. Nobody has been lost, but we are pushing the limits of what is safe. We try to remember that the difference between a fun day and a tragedy is just a few bone-headed decisions. We are knowingly putting ourselves into risky situation just for the fun of it. Our safety depends on staying aware of the FACETS that can trap us into making mistakes. It is when you are most confident that you are doing everything right that you need to step back and double check.